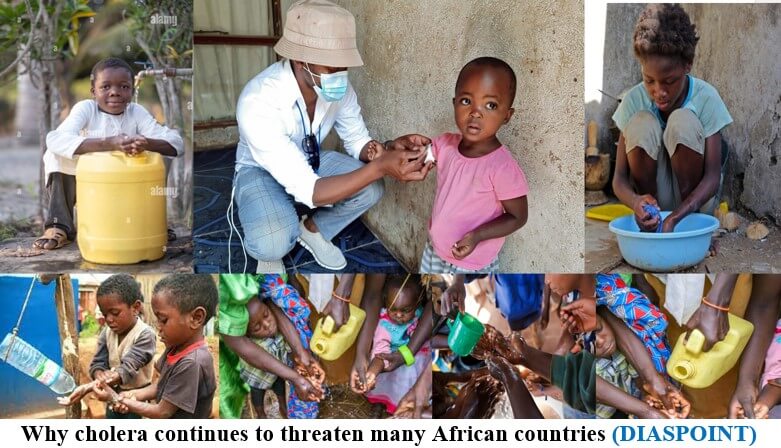

Why cholera continues to threaten many African countries

Malawi is facing its worst cholera outbreak in two decades. The outbreak started early in 2022 and has, so far, resulted in over 18,000 cases and the loss of 750 lives. It’s also forced the closure of schools and many businesses. Microbiologist Sam Kariuki, who is the director of Kenya’s Medical Research Institute, explains what cholera is and why it’s so hard to control in Africa.

Why is cholera still such a big issue for African countries?

Cholera is a disease caused and spread by bacteria – specifically Vibrio cholerae – which you can get by eating or drinking contaminated food or water.

It’s an old disease which has mostly affected developing countries, many of which are in Africa. Between 2014 and 2021 Africa accounted for 21% of cholera cases and 80% of deaths reported globally.

In several African countries, cholera is the leading cause of severe diarrhoea. In 2021, the World Health Organization reported that Africa experienced its highest ever reported numbers – more than 137,000 cases and 4,062 deaths in 19 countries.

Europeans, get our weekly newsletter with analysis from European scholars

It has persisted in Africa partly because of worsening sanitation, poor and unreliable water supplies and worsening socioeconomic conditions. For instance, when people’s incomes can’t keep up with inflation they’ll move to more affordable housing – often this is in congested, unsanitary settings where water and other hygiene services are already stretched to the limit.

In addition, in the last decade, many African countries have witnessed an upsurge in population migration to urban areas in search of livelihoods. Many of these people end up in poor urban slums where water and sanitation infrastructure remains a challenge.

Displaced populations – a major concern in several African countries – are also very vulnerable to water and food contamination.

It’s important to control cholera because it can cause severe illness and death. In mild cases cholera can be managed through oral rehydration salts to replace lost fluids and electrolytes. Severe cases may require antibiotic treatment. It’s vital to diagnose and treat cases quickly – cholera can kill within hours if untreated.

In 2015, it was estimated that over one million cases in 44 African countries resulted in an economic burden of US$130 million from cholera-related illness and its treatment.

What’s missing in the response?

African governments must acknowledge that the burden of cholera is huge. In my opinion, governments in endemic areas don’t recognise cholera as a major issue until there’s a big outbreak, when it’s out of control. They treat it as a once off.

The burden of cholera could get worse unless governments put measures in place to control and prevent outbreaks. They need to address water and hygiene infrastructure.