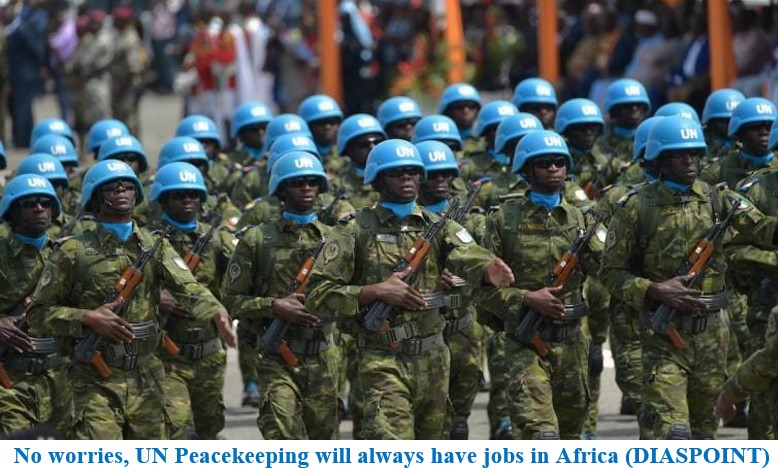

What Future for UN Peacekeeping in Africa after Mali Shutters Its Mission?

Post By Diaspoint | July 16, 2023

At Bamako’s request, the UN Security Council has begun drawing down the UN peacekeeping operation in Mali. In this Q&A, Crisis Group experts Richard Gowan and Daniel Forti explore the implications for blue helmet missions elsewhere on the continent.

In June, to the surprise of most UN Security Council members, Mali’s government called on the Council to pull UN peacekeepers out of the country “without delay”. Some diplomats briefly considered options for keeping the UN Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) in place, but most greeted the news with a resignation verging on fatalism. Although the precise timing of Bamako’s demand was unexpected, the Malian government had been frank about its loss of trust in the UN. But the move also reflected the fact that many members of the Council sense that an era of large, complex UN blue helmet missions in Africa is drawing to an end.

This era of peacekeeping dates back to the late 1990s, when the Security Council began authorising a series of UN missions to help end civil wars and support peace processes throughout Africa. Sizeable UN forces deployed in places from Sierra Leone to Sudan. By 2010, the organisation was overseeing more than 70,000 military and police personnel all over the continent. Despite many setbacks, this generation of UN missions helped end insurgencies, backstop elections and build peace in countries including Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. The missions were a success story for the UN, providing a sharp contrast to the earlier 1990s, when a prior generation of peacekeeping efforts in Rwanda and Somalia had ended in failure.

Most of these post-1990s UN missions shut down some years ago, but a few remain in place. Alongside MINUSMA in Mali, which started a six-month drawdown on 1 July, these include operations in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the Central African Republic (CAR) and South Sudan. Together, these “big four” missions still field more than 60,000 troops. MINUSMA, with just over 13,000 troops and police as of May, is the smallest of the quartet. Each mission faces political and security problems specific to the country where it is based, but all of them share the pathologies and pitfalls typical of large-scale stabilisation operations. Each has struggled to protect civilians in areas where its contingents are deployed. The missions have also lost political leverage, while enduring relations with host governments that are at best strained, and at worst hostile.

Read More from original source