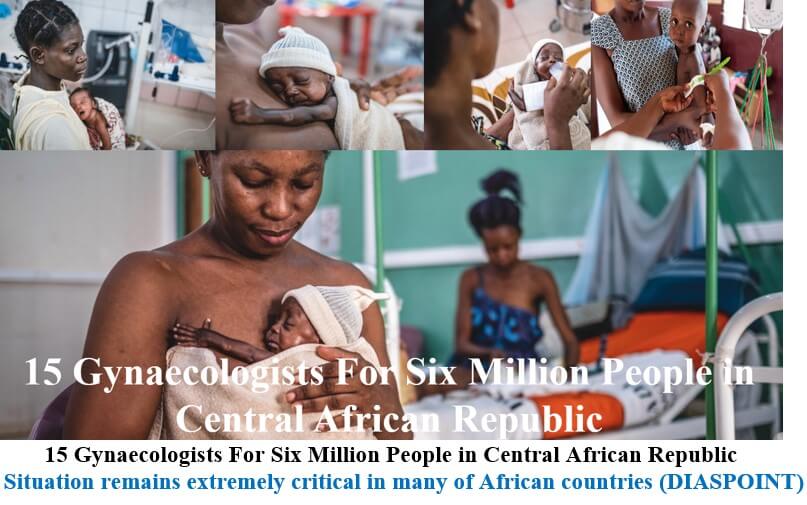

15 Gynaecologists For Six Million People in Central African Republic

Decades of instability and armed violence in the Central African Republic (CAR) have made essential medical care out of reach for many pregnant women and newborn babies. Overshadowed by the security situation in the country, tackling this everyday emergency is a priority for Doctors Without Borders (MSF) teams.

Divine has been labouring in pain for hours, her right hand clutching the bedpost, her left hand crumpling her orange and green loincloth. Her baby is overdue, and Divine is exhausted. In the labour ward of Bangui’s community hospital, the nurse has just administered oxytocin, a hormone to speed up the frequency and intensity of her contractions.

In this unit dedicated to high-risk deliveries, women are closely monitored by medics, who check their health and their baby’s heart rate every 30 minutes. If a woman’s labour goes on too long, she can be taken to the operating theatre for a caesarean.

Such attentive care is far from common for Central African women about to give birth. In a country which is severely short of health facilities and medical staff, few pregnant women have access to appropriate obstetric care.

“Many women do not go to a health centre for their delivery but give birth at home,” says Adèle Guerde-Seweïen, an MSF midwife at Bangui’s community hospital, known as the CHUC. “In this situation, complications can easily lead to the death of mother or child.”

An extreme situation

A scream, louder than all the other raised voices, rings out across the hospital ward. A woman has just learned of the death of her pregnant sister. Minutes earlier, she had been rushed to the hospital and taken straight to the operating theatre. But it was too late. The medical team did their utmost to stabilise her but only managed to save her baby.

“This tragedy would not have happened if she had had access to medical care in time,” says Guerde-Seweïen.

Maternal and neonatal health is a major health emergency in CAR. The country’s maternal and child mortality rates are among the highest in the world. According to the most recent statistics1, women are 138 times more likely to die of pregnancy and delivery complications in CAR than in the EU, while a baby in CAR is 25 times more likely to die before its first birthday than if it had been born in Europe.

15 gynaecologists for six million inhabitants

“In CAR, to be born or to give birth is to take a risk,” says Professor Norbert Richard Ngbale, an obstetrician-gynaecologist in the CHUC’s maternity and neonatology department. “There are only about 15 gynaecologists in the country, for a population of six million. There is a massive lack of qualified staff, especially in rural areas, where you mostly have traditional birth attendants who are not trained to detect complications.”

Most maternal deaths in CAR are related to unsafe abortions, but also to pregnancies that occur too early (i.e. when the girl or woman is too physically immature to give birth safely) and to giving birth at home. Many of these could be avoided if healthcare was available, either in terms of pregnancy support or family planning provision. CAR’s chronic medical emergency is also fueled by extreme poverty: although maternal and child healthcare is officially free in CAR, too often, it is only available to those who can pay.

“In a country where 70 per cent of the population lives on less than US$2 a day, every decision must be weighed up financially, even if it means putting one’s health at risk,” says René Congo, MSF head of mission in CAR. “For patients, going to the hospital is an expense. They don’t have money to pay for antenatal care, nor for transport to the hospital, let alone for the delivery. Many women think it is better to go to the hospital at the last minute, if at all. Supporting the provision of free care is therefore vital.”

“This time, I wanted to avoid any risk”

As a mother of eight who experienced complications in childbirth with her seventh baby, Carine Dembali did not want to risk arriving too late at the hospital this time.

“With the exception of my first child, I have always given birth at home due to lack of money,” she says. “But the last time, there was a problem. My baby came out but the placenta didn’t. My family rushed me to Castor’s [a hospital with a maternity ward previously managed by MSF], where I didn’t have to pay anything. That’s why this time I wanted to avoid any risk. I went to the hospital near my home before the delivery. They saw that the cord was threatening my child and I was brought here for a caesarean.”

The CHUC’s maternity and neonatal wards, which were fully renovated by MSF before opening in July 2022, provide emergency care to pregnant women and newborns in critical situations. From mid-July to Mid-December, MSF and the Ministry of Health teams provided care to 3,084 pregnant women, and 860 babies were admitted to the neonatal ward, including 239 born preterm.

Few hospitals in the country provide a similar service, including an intensive care unit for premature babies and newborns with trouble breathing and other complications.

Archange, who was born at just 28 weeks (compared to a normal gestation of 38-40 weeks), fought for his life for 45 days in the intensive care unit of the CHUC. The medical team were so impressed by his fight to survive that they nicknamed him “little general”.